By: Gavin Swift

Introduction:

A wise man once said:

“Let’s talk about scales, baby –

Let’s talk about you and me,

Let’s talk about major, minor,

Pentatonic, and blues baby,

Let’s talk about scales”

Man that guy was so wise. Howdy! Today we’re going to be covering and discovering the scales of the piano!

By investigating this crucial element of musical theory, we’re able to better compose our own music, and able to better understand the music of others that we might be essaying to learn. Scales are also the OG of finger exercises and training if you’ve got a bit of a Evgeny Kissin type dream going on (I’m personally trying to model his hair) and will teach you the curves and crevices of the piano keyboard in the most beautiful way!

So, if you’re all set to learn, let’s meet at the piano and get stuck in!

What are piano scales?

My friend, you’re not ready yet. First let’s answer:

What are scales?

Great question. A scale is simply a collection of notes played in a particular (usually consecutive) order. We often refer to scales by the key that they belong to – a key being a collection of notes where a certain tone feels like the central or home tone. For example, in both C-Major & C-Minor, the central or home tone is C. We also call that central tone the tonic. Or, just to make this super accessible for everyone, we might number it as ‘1’.

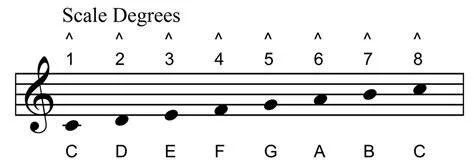

Take a look at the image below:

Now every white note on that keyboard belongs to the key of C-Major. We’ll use this to jump into our study of…

Major Scales

If you were to play:

E, D, C, D, E, E, E, D, D, D, E, G, G (that stone cold classic Mary had a Little Lamb)

You would be playing a tune in the key of C-Major.

But you would not be playing a C-Major scale. The C-Major scale has to be the notes played in the order below:

Or that sequence in reverse – so ascending or descending. Which brings us to some of that sweet musical etymology we so love to explore! The word scale comes from the Latin scala meaning steps, staircase, or ladder. So we can think of a scale in this way! In the C-Major scale above, the first and last rungs of the ladder are C, our home rungs, everything between those guys are essential steps.

So what’s a piano scale?

Yes. You’re ready now. A piano scale is just the above information applied to a piano keyboard. Maybe I was wrong ok?! Maybe you were ready!

What other types of scales are there?

The short answer is, there are many different kinds. The good news is that to learn a scale, learning the individual notes is less important, than learning the pattern of each scale. To illustrate this, let’s look at our friend C-Major once more:

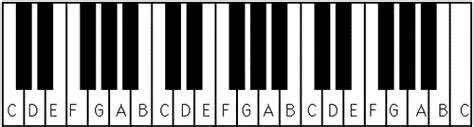

And just in case you’re not sitting at a keyboard:

Now we already know that the C Major scale consists of every white key on the keyboard played in consecutive order. So playing every white note going up and every white note going down on the keyboard above would give us a great example of the C Major scale.

Now notice above, that between certain notes (C&D, D&E, F&G, G&A, A&B) there are black notes, but between other notes (E&F, B&C) there are no such obstructions. These black notes are the sharps (#s) and flats (♭s) of the keyboard.

We call the distance between a white note and a black note (say, C to C#) a semi-tone, or half-step, and we call the distance between two notes obstructed by a half-step (for example C to D) a whole-tone, or whole-step. So two half-steps = one whole-step.

Keeping our eyes on the diagramatic prize above, we can see that the pattern of the C Major scale clearly goes:

Now that pattern:

1 whole-step 2 whole step 3 half-step 4 whole-step 5 whole step 6 whole-step 7 half step 8

Now wait for it…

…

…

…That’s the pattern of every single major scale every created on this sweet planet called earth. Whoa.

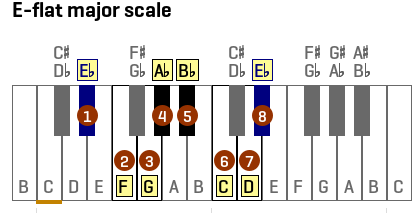

Don’t believe me? Check out this E♭-Major Scale:

So what’s the pattern here? Follow along with me:

E♭ – F = whole-step; F – G = whole-step; G - A♭= half-step; A♭-B♭= whole-step; B♭-C= whole-step; C-D= whole-step; D-E♭ = half-step.

Didn’t I tell you! Isn’t music glorious?! Now a quick bit of info about Major scales:

Major scales are generally described as sounding ‘happy’ or ‘positive’.

The reason that they’re called Major scales, is because these scales consist primarily of larger, or Major-er intervals (an interval is the posh word we use to describe the distance between notes).

Now for your first assignment!

Assignment 1:

Sit down to the keyboard (I love you if you’re already there – if you’re not, I still love you)

Try to play every major scale by starting at all the different notes and applying the major scale pattern. You might find it easiest to work through all the white keys before moving onto the black ones – or maybe you’d like to move chromatically. Either way, take the time to practice and bed in this awesome scale pattern!

The Chromatic Scale

Now logic probably says that following on from the Major scale we should look at the minor scales – but not me! I laugh in the face of danger! Who needs logic anyhow! (2)

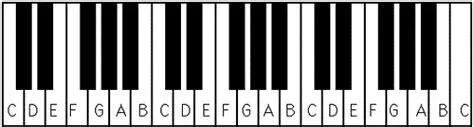

The chromatic scale is cool. The chromatic scale can start on any key (as can any scale really), but consists only of half-step intervals! So a chromatic scale starting on C on the diagram below:

Would then play C#, followed by D, followed by D#, and so on, until you reach the very top C having played every single note in between. Pretty awesome right?! Here’s how a chromatic scale looks when it’s notated:

The above shows a chromatic scale starting on C both ascending and descending for one octave.

Assignment 2:

Get thee to a piano keyboard!!!

Start on the lowest note available at that keyboard – if you’re at full size piano this will most likely be A.

Play a chromatic scale ALL THE WAY TO THE TOP of your keyboard!

What goes up must come down! Now play a chromatic scale ALL THE WAY DOWN your keyboard!

Easy Rachmaninov – you’re sounding great!

The Minor Scale(s)

Oh no! Why is there an S in parenthesis?!

No, don’t be afraid!

I’m kidding, be afraid!

No really don’t be afraid! Although when you hear this scale (or scales as we’ll see) you might get a twinge of fright! While Major scales are associated with positive, happy, sounds, minor scales are generally associated with negative, or gloomy sounds – sometimes they can also sound downright scary! Don’t believe me? Check out this performance of Bach’s Toccata & Fugue in D minor – which essentially begins with a descending D-minor scale!

Now.

Let’s deal with that parenthesis.

You see, there is not one, not two, but THREE variations of the minor scale! (Play first phrase of Toccata & Fugue in D minor for scary effect there)

The three variations are:

The Natural (or ‘Aeolian’) minor scale

The Harmonic minor scale

The Melodic minor scale

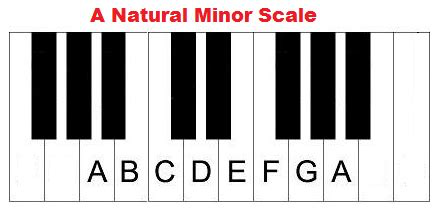

The Natural Minor Scale

Iiiiiiinnn tthhhheee red corner! Is the natural minor scale. Let’s take a look at the A minor natural scale. Which, lucky for us, consists entirely of white notes, just like C-Major!

Or in notation, it looks like this:

The pattern for this scale is:

(Tonic) Whole-step, half-step, whole-step, whole-step, half-step, whole-step, whole-step (tonic).

So actually, this scale has the same number of half-steps as any old Major scale! What’s changed is there position in the scale, happening at the second and fifth intervals. Groovy. Now let’s peek at…

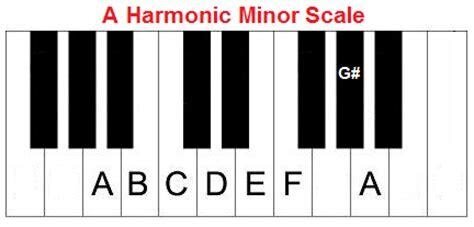

The Harmonic Minor Scale

Ok. So let’s stick on A minor and check out the A harmonic minor scale:

Or in notation it looks like this:

Ok! So who can spot the difference here?!

I’m sure you’ve all seen it, but I’ll be captain state the obvious. What the hey-ho is that G# doing there?!

I’ll tell ya.

In a harmonic minor scale we raise the 7th note by a half-step, essentially increasing the interval between notes 6 & 7 to a distance of 3 half-steps. Whoa!

Why??? And why isn’t that G# listed in the key signature like you’d expect?

Both very valid questions! If we can let’s answer it with a practical experiment. At your keyboard, play the note G, followed by the note A. How does that sound? Pretty good right? Pretty pleasing? Well hold onto your harmonics, because now I want you to play G# followed by A…

…Did you do it? Oh my gosh how did it feel? Did you get that level of oomph that we all know and love? In essence, that 7th is raised because it feels so good to resolve to the tonic or central tone from a raised 7th. Remember, the root of the word harmony in music stems from things literally working better together sonically – i.e. harmoniously. So when we see the word harmonic attached to something in music theory, you can usually bet you bottom B♭ that it’s because it will sound straight up pleasing. That’s also the reason that this is the most commonly used form of minor scale in Western music!

Why isn’t the raised 7th in the key signature? Well, technically because it’s not in the key. Remember, in a key signature, the first note we would mark as sharp (where appropriate) will always be F. And the first note we would mark as flat would always be B. Well looky here! G# is neither of those! Therefore it’s place in this scale is as a function of harmony rather than key. Phew. This is some heavy stuff.

The tone pattern for a harmonic minor scale is as follows:

(Tonic) Whole-step, half-step, whole-step, whole-step, half-step, three half-steps, half-step (tonic).

Rad.

And finally,

The Melodic Minor Scale

Probably in my top three variants of minor scales this guy packs a major punch (sorry).

In the melodic minor scale we continue to raise the 7th note of the sequence by a half step, but, we also raise the 6th a half step!

Melodic minor scale, you loco!

But the madness doesn’t stop there! Not by a long chalk! You see on the way up we raise (or sharpen) the 6th and 7th notes by half a step, but on the way down we lower (or flatten) them back to the natural minor sequence. Before you spit out your chicken soup all over the keyboard, let’s take a look at it in the form of a diagram. Just cause we’re so cosy with it, we’ll use the A minor melodic scale:

And as we said, on the way down that F# and G# would become a G♮ and a F♮. To further clarify, let’s see it notated:

Muy infuego. Spicy like a curry.

‘But why?!’

Why indeed! Ok, remember how in the melodic minor scale we saw how that G# to A felt soooooo good (*drool emoji*), well that’s because it instructs the ear to the central tone, the tonic of A in this case. When we flatten the 6th and 7th notes on the way down, this leads our ear to the 5th note, otherwise known as the dominant; in this scale the dominant is E.

Now in a scale, the dominant is the centre of primary discord against the tonic, which is a fancy way of saying it feels incredibly good to resolve from E to A, or any dominant to any tonic. So when we flatten the 6th and 7th going down, we get a sonically greater pay off when we arrive at A, because we’ve had another ‘feels so good’ moment (*drool emoji*) at 6 – 5.

That’s also the reason that this scale is named ‘melodic’! Because that type of phrasing in a melody works incredibly effectively!

3: The final assignment! (3)

Go to your keys!

Try playing through all of the variations of the minor scales. Sure it might be a big as do on every note (12 available pitch classes multiplied by 3 variants of minor scales…arghh!!! My head is exploding with the maths!!!) but even just doing it for A will teach you a cool lesson.

See if you can identify these patterns in any music that you might know and love! I’ll get you started – I love the use of the melodic minor scale in The Beatles (google them) track Yesterday. What other ones can you find!

Conclusion

We’ve covered a lot today! And this is only the tip of the iceberg of scales! We’ll be looking at a few more examples in further lectures, but if you curiosity is simply unquenchable, why not have a trawl of the internet to see what other kinds you can find!

Happy learning! And most importantly, happy playing!!!

For today, remember, every day in life is filled with new assignments. Never has that been truer than in your study of the art of noise.

(1) Marcus Aurelius definitely never said that. But I did. So there.

(2) We all do. I, perhaps, need it the most.

(3) For today, remember, every day in life is filled with new assignments. Never has that been truer than in your study of the art of noise.

Gavin Swift is a film and media composer based in London, England